Look back: Indigenous wisdom heals people, Mother Earth

Revisiting and Applying the Universal Values of First Nations in Pursuit of Healing

By Dr. Marivir R. Montebon

This paper, written in 2023 for my doctoral class on Ethics in Ministerial Leadership under Dr. Jacob David, revisited the universal value systems of First Nations in the US and the Philippines - particularly their ethics on faith, self, community, and the environment as living testaments of and tools for personal, communal, spiritual, and environmental healing.

I focused on the shining examples of two indigenous leaders whom I have personally encountered - educator Patricia Anne Davis of the Navajo Tribe and Philippine Congressman Teodoro Baguilat of the Ifugao Region. I also included the life and activism of Winona LaDuke of White Earth Reservation in Minnesota using secondary sources to provide perspective on environmental healing and women’s leadership.

The actionable proposal of this paper is to integrate literature and education programs of holistic indigenous practices in schools and nonprofit organizations, starting with small groups of postmodern students, professionals, friends, and family to reeducate themselves on the ways of the First Nations toward personal, community, and environmental healing. These are small baby steps to return to the wisdom of the indigenous past to find healing and transformation in a world that has become sticky with individualism, exploitation, competition, and greed.

My Theological and Ethical Standpoints

From an ethical standpoint, I believe that much attention must be given to the American Natives or the First Nations of America – whether by government or individuals. They are the poorest and most underserved in American society. Yet, we have so much to apologize to them in every way we can - and learn from their diminishing culture and heritage.

This paper proposes that modern-day pedagogy must institute the holistic values of self-respect, love for Mother Nature and community, and cooperation inherent in the culture of indigenous peoples. In photo, Ifugao leader and former congressman Teodoro Baguilat, Jr.

It is imperative to include the rich traditions and cultures of the First Nations back into our modern life and in school curriculums from elementary throughout graduate school because indigenous wisdom is key to heal society’s misery. Modern-day pedagogy must institute the holistic values of self-respect, love for Mother Nature and community, and cooperation inherent in the culture of indigenous peoples.

The current brokenness of self and the disintegration of families and communities are nourished by the false notions of ego, individualism, and greed[1] – which to me are results of a material and consumerist culture that has both drastically eradicated the rich culture of the First Nations.

How do we heal ourselves in this kind of society? Perhaps, we could look at the very First Nations who existed long before colonialization and industrialization to give us an answer. As an African proverb goes: “To go back to tradition is the first step forward.”[2]

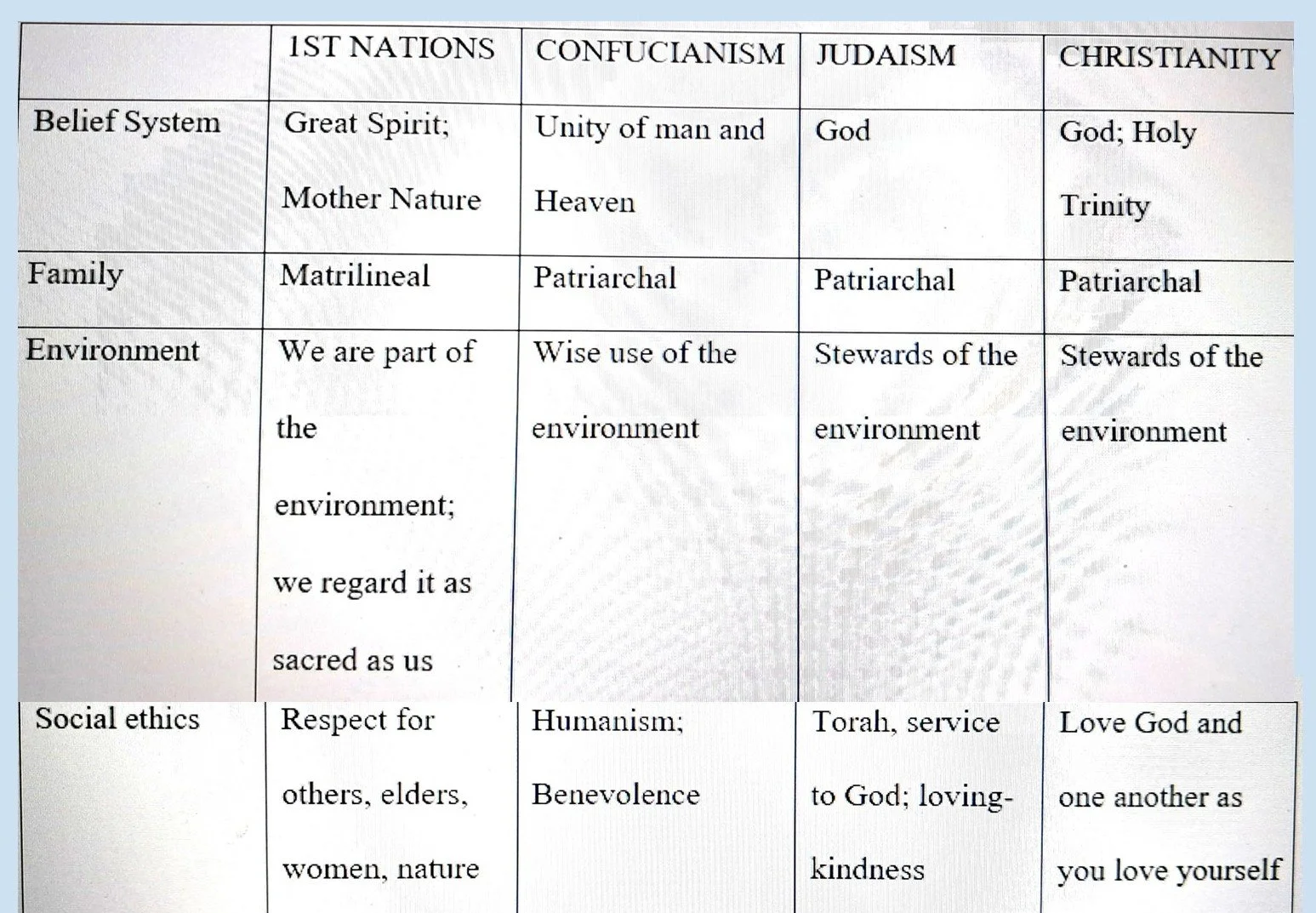

I adhere to the First Nations ultimate regard of the Great Spirit, Mother Nature, and the self as sacred and thus must be revered.[3] This is shared by Judaism in its regard for humanity as stewards of the Earth[4] and Christianity’s theological foundation whose main message is to love God and one another.[5] The Native American’s ethics of respect for the self and others is shared by the foundation of Confucianism as well.[6]

This table summarizes the belief system, family, environment, and social ethics of the First Nations, Confucianists, Jews, and Christians. What is clear is the First Nations coherent respect with Mother Nature and women, in contrast to absence of such in the patriarchal systems of Confucianism, Judaism, and Christianity.

The Native American Code of Ethics goes back to some 11,000 years which regards women equally with men, as they regard Mother Nature with reverence, being an integral part of the natural environment.

The wisdom found in the Native American Code of Ethics goes back to some 11,000 years. It is deep yet simple and uncomplicated to understand and adhere. It regards women equally with men, as they regard Mother Nature with reverence.

The Code guides the Natives to be prayerful (which in Christianity is the basis of one’s relationship with God – prayer), accepting and forgiving, genuine, to never steal, respecting of everyone, be kind, and regard Nature as part of us and borrowed from our children.

As summarized by Australian life coach Ronit Barras, this is the Code of Ethics of the First Nations in the America: [7]

Rise with the sun to pray. Pray alone. Pray often. The Great Spirit will listen if you only speak.

Be tolerant of those who are lost on their path. Ignorance, conceit, anger, jealousy, and greed stem from a lost soul. Pray that they will find guidance.

Search for yourself, by yourself. Do not allow others to make your path for you. It is your road, and yours alone. Others may walk it with you, but no one can walk it for you.

Treat the guests in your home with much consideration. Serve them the best food, give them the best bed, and treat them with respect and honor.

Do not take what is not yours whether from a person, a community, the wilderness or from a culture. It was not earned nor given. It is not yours.

Respect all things that are placed upon this Earth – whether it be people or plant.

Honor other people’s thoughts, wishes and words. Allow each person the right to personal expression.

Never speak of others in a bad way. The negative energy that you put out into the universe will multiply when it returns to you.

All persons make mistakes, and all mistakes can be forgiven.

Bad thoughts cause illness of the mind, body, and spirit. Practice optimism.

Children are the seeds of our future. Plant love in their hearts and water them with wisdom and life’s lessons. When they are grown, give them space to grow.

Avoid hurting the hearts of others. The poison of your pain will return to you.

Be truthful at all times. Honesty is the test of ones will within this universe.

Keep yourself balanced. Work out the body to strengthen the mind. Grow rich in spirit to cure emotional ails.

Make conscious decisions as to who you will be and how you will react. Be responsible for your own actions.

Do not touch the personal property of others. This is forbidden.

Be true to yourself first. You cannot nurture and help others if you cannot nurture and help yourself first.

Share your good fortune with others.

We are all living together in the same land, sharing the same space. This makes us the custodians of this land, not the owners, not the destroyers and not the conquerors. Nature is not for us; it is part of us and so are others. It is for our children too.

Background

Sometime in 1999, I covered an international summit of indigenous communities for the protection of watersheds in my birthplace Cebu City in the Philippines. The event was a turning point for me - the First Nations of the world, particularly in Canada and the Philippines – offered a consistent world view and lifestyles that preserve their wholeness of being and their physical world. I thought their ancient wisdom was a clear solution to problems of moral and environmental decay.

That world gathering gave me a clear picture of who indigenous peoples are. I was awed by them. I believe that for us modern humans to survive poverty (of body, mind, and spirit), inequality, and the onslaught of natural disasters, we need to look back and see how the indigenous peoples conducted themselves: with calm and dignity and utter respect for themselves and each other - before their remnant communities fully vanish from the world.

Patricia Anne Davis - Healer from the Navajo Tribe

Many years later, in 2013, I met a healer from the Navajo Tribe in New York City.

I will always remember Patricia Anne Davis – the one who serenely told us in a gathering of media and women leaders – “Americans are partying on our sacred land.” It’s a bitter truth to swallow, and something which every immigrant ought to know.

Patricia Ann Davis of the Navajo Tribe

Immediately, it all came clear to me through Davis’ gentle voice. America is standing on sacred lands of the Native Americans and empowered by the slavery of the blacks and other minorities. Can anyone handle the truth?

But Patricia Anne Davis didn’t sound bitter. When I asked how are reparations to be made and justice be served to you, Native peoples? She said, “We must go back to our sacred selves if we are to transform society.”

Davis was one of the panelists of an indigenous groups conference of Canada and the US. From the Dineh/Navajo tribe, gentle-mannered and soft-spoken Davis has a native name that translates to “peacemaker” or “one who greets others with peace.” She uses her native name only in sacred spaces during rituals.

Born in Arizona and raised in New Mexico, Davis became her father’s heiress of wisdom and heritage. She regarded him (also a healer in their village) as her life-long teacher from her birth until he passed away in 1983.

Davis descended from the Mississippi Band of Choctaw-Chahta and born to the Taa chii nii and Kii yaa aanii kinship families of the Navajo/Dineh Nation. Davis’ maternal grandparents are Chahta, and her paternal grandparents are the Kii yaa aanii clan of the Dineh. She has become an international teacher and healer by tribal lineage, training, and initiation.

Davis earned her bachelor’s degree in Psychology from the University of Arizona and an MA in Whole System Design (the language and techniques of creative change), from the Antioch University in Seattle, WA. [8]

Davis’s words continued to resonate with me eight years later. She said gently: “We are all currently living in a parasite system. But the age now is breaking the silence, because in the tribal language, submission-domination does not exist. And it has been proven that the win-lose situation does not last long, it creates imbalance. We break our silence by using the power within us.”

As a guest panelist, Davis responded to the deep concerns of two women leaders from the First Nations of Canada to protect their lands and lives, particularly with the continued incursion of their lands by big developers. She emphasized that “there is a need to go back to the philosophy of the ‘power within’ and do away with the ‘power over’ that is prevalent.”

The Navajo worldview is that ‘power within’ is one’s internal power or capacity while ‘power over’ is the dominating kind of power over someone or a group. [9]

The second time I met Davis was in a much fresher environment - at the upper west side of Central Park. In that healing session, I learned that there was something deeper than the noble cause of fighting for justice. Davis was telling her small group of participants that reclaiming justice meant “going back to the sacred self. It is what will truly heal the world.”

That gave me a profound awakening.

She spoke: “The world is imbalanced, broken. We make it whole again by going back to our sacred selves. Healing is a state of harmlessness. We do not fight war with war. The cycle of imbalance will continue. The key is to go back to the sacred self, the reverence that all in life is whole and holy and founded on love and positivity.”

Davis: To go back to the natural system of life is key, back to the Divine Feminine, where there is no domination-submission, where the feminine as the giver of life is supported and protected by man. “It used to be that way, until the parasitic belief system took over to subjugate Mother Earth.”

Davis emphasized on adhering to a natural system of life. “The natural system is the one belief system. We are all part of the divine and the natural flow of things. And so, we go back to the concept of the Divine Feminine, where there is no domination-submission, where the feminine as the giver of life is supported and protected by man. It used to be that way, until the parasitic belief system took over to subjugate Mother Earth.”

According to Davis, the belief systems of religion, philosophy, and academic theory were responsible for the current parasitic system. But she also warned that modern-day activism is a limited and same level engagement to counter the status quo.

“One has to be an advocate for a win-win situation. I am thus an advocate, not an activist. Activism only means to equalize force against force. One has to raise a political consciousness into the more sublime, holistic view.”[10]

Davis said that political engagement in trying to resolve a social problem is limited and linear. It falls in the same genre of energy, a contest of political might. Corruption, for instance, may be addressed by removing an errant leader from public office through a political will and a legal process. Corruption must be curbed personally too by members of the community at large to cleanse society holistically.

Davis was setting the stage for world-wide consciousness of the wisdom of natural thinking, in places that are regarded sacred, such as where we were at the expansive shade of the Cedar tree in Central Park.

With the mindset of natural thinking, healthy eating habits could set in, mind de-stressing activities are being studied and applied, and a positive outlook and respect for others take place in everyone.

In many sacred spaces in the US, and in the world, the rebirth of holistic thinking is taking shape, through the advocacy of Patricia Anne Davis, and other like-minded advocates. This for me is a beautiful transformation of humanity - slow and authentic.

Davis had worked in the Health and Human Services profession in Behavioral Health, Social Services and Mental Health for over 20 years. She was the original writer of “The Beauty Way Curriculum” K-12 Prevention Education for alcohol and other drug recovery and wellness restoration which was published in 1990 and written in English and Navajo language.

She is a private practitioner, diagnostician, international teacher, and consultant of Navajo/Dineh blessingway ceremonial healing principles that are cross-cultural, intergenerational, inclusive, and universal in practical application. Her blessingway ceremonies are Living the Loving Way, Walking in Beauty, The Ceremonial Change Process, Wealth care, and Love Currency. [11]

Davis translated the Dineh blessedway ceremonial principles into an Indigenous Ceremonial Change Process (ICCP) to facilitate a healing process that is not coping, but correction of any out-of-balance conditions within people, society, or the environment.

She designed presentations, training, ceremony, and workshops within the context of the natural order and indigenous science, a concept from the literature to define a distinction between an Affirmative Thinking system and a Eurocentric Dualistic thinking system.

The ICCP intends to reframe win-lose destructive and death-producing choices and decisions into win-win constructive and life-affirming choices and decisions with unifying principles on inclusion of all ethnic nationalities, cross-cultural, inter-generational, restoring resources to the next generation of youth, universal practical life application and can be translated into any language. Davis has been well-received in nine countries where she taught the ICCP.[12]

Teodoro Baguilat Jr. – the Only Indigenous Congressman in the Philippines

Fifty-five-year-old Teodoro Baguilat Jr. or Teddy to family and friends is an Ifugao and Gaddang by ethnicity and is the only representative of indigenous minorities in Philippine Congress. He finished Journalism at the University of the Philippines and has an extensive background in the executive arm of government.

Former Congressman of the Philippines, Teodoro Baguilat, Jr. of the Ifugao province.

Baguilat’s entry to public office began in 1992 as councilor in his hometown in Kiangan, and then as mayor from 1995-2000. He was governor for the Ifugao province from 2001 to 2010.

In his watch, the Ifugao province was taken out of the list of 10 poorest provinces in the Philippines his stint as governor. Likewise, the Cordillera Rice Terraces, considered as the 8th wonder of the world by the UNESCO, was delisted from its endangered status during his leadership.

He held international offices - such as being president of the Global Indigenous Community Conserved Areas Consortium and vice president for Asian Forum of Parliamentarians for Population and Development.

Baguilat became the congressional representative for the Ifugao region from 2010-2019. He authored and co-authored 62 bills that promoted and protected the human rights of the minorities, women, and LGBTQ communities. He also helped pass green legislation that ensured the health of the watersheds and protection of cultural minorities. [13]

In November 2021, I had the chance of interviewing the congressman, who is based in Quezon City in the Philippines, over Issues & Inspiration, a digital show that I co-produce and co-host. He shared his experience on how the indigenous communities tried to create a balance of survival and protecting the more than 2000-year-old Cordillera Rice Terraces which essentially meant preserving the ancient cultures that thrived in the mountain provinces long before Spanish colonialization. [14]

It was hard, he said during the 40-minute interview, because they had to deal with massive diaspora of natives and the extreme budgetary need to physically restore the rice terraces from erosion as an aftermath of two earthquakes and water poisoning because of the use of pesticides and mechanical farming.

In ancient times, Ifugao farmers fully lived and thrived producing heirloom rice varieties that can withstand harsh climate conditions like storms or droughts. Their rice produce, as well as fruits and vegetables, flowers, and livestock sustained their generations for more than 2000 years. The tedious and sacred way of producing rice was done per family and the spirit of cooperative farming among neighbors and clans is alive to this day. Older generation of farmers kept their 90% of their rice and other produce for their own consumption and sold only about 10 percent. They were stable that way. Towards the 1970s, with the introduction of high yielding varieties of rice, the new generation of farmers sold more than half of their rice production for cash but also became indebted because of the need to purchase pesticides and fertilizers. Imbalance in local economies began as well as soil erosion, water poisoning, and pestilence.[15]

A friend of mine, New York-based June Pascal, who made a pilgrimage to the Cordilleras in 2014, was in awe in telling me that the Ifugao people do not need the outside world to be healthy and happy as they are. As far as her eyes can see, she said that the indigenous people in the upper Ifugao region, continue to thrive while those in the lower lying areas who decided to buy into the commercial high yielding varieties of rice that came with the necessity of buying pesticides and fertilizers were experiencing high cost of production and eventual crisis.[16]

With Spanish colonization and modern-day industrialization, the Ifugao region was torn between maintaining their indigenous culture and living in the present-day demands of modernity. Baguilat said that he tried to make some compromise agreements with each family by encouraging them to decide that at least one member should be appointed to continue the farming and cultural practices in the Cordilleras.

Cordillera rice terraces in the Philippines

As governor and later as congressman, he also provided budget for the rehabilitation of watersheds in the region. Painstaking groundwork must have paid off, as the UNESCO delisted the Cordillera Rice Terraces as an endangered habitat.

Baguilat is among the rare breed of public servants in the Philippines who has an illustrious record of integrity. In May 2022, he is seeking a senatorial seat in the Philippines, which is a rather steep electoral arena for Philippine Senate is a battleground for Filipino oligarchs, just like the presidential and vice-presidential offices.

Asked how he is meeting the challenge in the titanic fight of elites in the Senate, he said that persistence and clarity of vision are his main messages, especially for the youth who are desperate for visionary leadership and integrity.

Baguilat emphasized that he will focus on history and values education for the Filipino youth. The academic sector must provide for such enlightenment and inspiration for the young people, he said. The indigenous values of love and respect for self, the others, and the environment cannot be overemphasized and must have practical ways of application in daily living.

Baguilat’s wisdom is shared by African American respected teacher and church leader Grant Shockley in the US. Shockley is a luminary in the black academic and church community who emphasized the need for black children to be taught about the history and come up with a holistic ministry of songs and curriculum and social concerns.[17]

In the book In Search of Wisdom: Faith Formation in the Black Church, Smith cited Shockley who advocated that “wisdom formation today for the sake of present and future wise decision making must be built on the wisdom of the past, thus black children must be taught of the truth about their history to preserve their rich heritage.”[18]

Baguilat said it was disturbing for him to look at the prevailing mindsets being propagated in social media in the Philippines these days: “that a corrupt leader is okay for as long as he has done something for the society; or it is okay to lie for as long as you get things done.” We can do so much better for our youth, he noted.

At the time of his own soul-searching, Baguilat asked the permission of his parents (who raised him in Manila) to go back to his ancestral roots in the Ifugao Region when he was 13 years old. “I felt empty. I thought that there was something lacking in my life. I decided to go back to the Cordilleras. There I found my meaning. I found what I am supposed to do,” he said in the Issues & Inspiration interview.

Baguilat had come a long way since then, doing what he can to preserve his rich indigenous traditions while making sense of what modernity has done to Filipinos and Philippine society.

Davis and Baguilat have presented a holistic and coherent analysis of societal ills and solutions to human misery. They view themselves and their race simply as one - interrelated and uncompartmentalized. The self is sacred as Mother Nature and Great Spirit are sacred and so is everyone, including plants and creatures, and thus must be respected.

LaDuke: Healing Mother Nature Necessitates Women in Leadership

The various movements to address environmental problems, for indigenous peoples, is essentially a concern of women. Winona LaDuke of the White Earth Reservation in Minnesota articulated this during the 4th World Conference on Women at the United Nations in 1995.[19]

Following the wisdom of her tribe, she said in her speech: “The Earth is our Mother. From her we get our life and our ability to live. I am taught to live in respect for Mother Earth. In Indigenous societies, we are told that Natural Law is the highest law, higher than the law made by nations, states, municipalities, and the World Bank. That one would do well to live in accordance with Natural Law. One of our Great Leaders – Chief Seattle – stated that what befalls the Earth, befalls the people of the Earth.”

LaDuke, who is an educator, activist, and writer, viewed that the plunder of the Earth originated with exploitative relationship promoted by industrialization. In her words: “the predator-prey relationship that the industrial society has developed with the Earth, and subsequently, the People of the Earth.”

She expounded in her speech by saying that this relationship found its negative impact on women. “We, collectively, find that we are often in the role of the prey, to a predator society, whether for sexual discrimination, exploitation, sterilization, absence of control over our bodies, or being subjects of repressive laws and legislation in which we have no voice.”[20]

LaDuke postulated that there is a need to seek and struggle for common ground among women as an integral part of the struggle to save Mother Earth. “The only matrilineal societies which exist in the world today are those of Indigenous nations. We are the remaining matrilineal societies. Yet we also face obliteration.”

“Simply stated, if we can no longer nurse our children, if we can no longer bear children, and if our bodies, themselves are wracked with poisons, we will have accomplished little in the way of determining our destiny or improving our conditions,” she warned.

LaDuke is an Anishinaabekwe (Ojibwe) enrolled member of the Mississippi Band Anishinaabeg. She was born in Los Angeles on August 18, 1959, to activist parents Betty Bernstein and Vincent LaDuke, also known as Sun Bear, of the Anishinaabe (or Ojibwe) from the White Earth Reservation in Minnesota.

As a young child, LaDuke went to powwows and many tribal functions with her father which created a deep and lasting impact on her. Although her parents divorced, she continued to spend summers in native communities of her father. In her student life, she became involved in the campaign to stop uranium mining on Navajo land in Nevada. There was no turning back since then.

LaDuke graduated in 1982 from Harvard University with a degree in rural economic development. She also completed a master’s degree in community economic development at Antioch University in 1989.

While working as principal of the reservation high school at the White Earth Ojibwe reservation in Minnesota, LaDuke became an active part of the Anishinaabeg people’s struggle to recover lands by an 1867 federal treaty which covered 837,000 acres. By 1934, non-Native groups and lumber companies took over 90% of their lands. After four years of litigation, Anishinaabeg people lost their claim.

The lawsuit’s failure only emboldened LaDuke to dedicate her life to protect Native lands. She helped establish the Indigenous Women’s Network (IWN) in 1985 where she was also co-chairperson. This network is a coalition of 400 Native women activists and groups aimed at making Native women visible and empowered to take active roles in tribal politics and culture. The IWN strives both to preserve Indigenous religious and cultural practices and to recover Indigenous lands and conserve their natural resources.

In 1989, LaDuke founded the White Earth Land Recovery Project (WELRP) which is funded by the Reebok Foundation. WELRP buys back reservation land that’s previously purchased by non-Native people to foster sustainable development and provide economic opportunity for the Native population. It is now one of the largest reservation-based nonprofits in the country.[21]

Changing Our Ways of Life

Although continuously facing the threat of extinction, Native peoples all over the world are taking responsibility to have their voices heard and rich heritage promoted. I see hope for us all humanity in the First Nations relentless struggle to protect Mother Nature and for justice.

During the pandemic, the Ifugao region experienced abundance. The lockdown meant that the natives had more time to take care of their farms. As a result, they had enough supply of fresh produce and farm products for urban markets, including the capital Manila.

Baguilat and Filipino youth after an environmental and youth meeting.

Congressman Baguilat, during our interview, happily recounted that even to this date, his marketing campaign called Cordillera Landing on You (inspired by the Korean romantic series on Netflix Crash Landing on You) has continued to flourish and expanded markets for fresh agricultural products in the north and central Luzon in the Philippines.

The bountiful harvests from the Cordillera Rice Terraces are a silver lining in the pandemic. Baguilat said that the Natives are getting busier these days in their farms and delivering goods to customers.

The likes of Baguilat, Patricia Anne Davis, and Winona LaDuke are to be emulated for their steadfast dedication to promote indigenous peoples deserved space in the world.

The Church as an Institution to Defend Indigenous Peoples

The United Methodist Church’s vocal stance and high regard for the welfare and rights of the American Natives is highly commendable. In a comprehensive document passed in 2016 titled ‘Native People and the United Methodist Church’, its General Conference affirmed “the sacredness of American Indian people, their languages, cultures, and gifts to the church and the world. [22]

Beyond rhetoric, the UM Church outlined ways in dealing with the First Nations of America, after acknowledging the wrong doings of European colonialists, including Methodists and Catholics, that used the Doctrine of Discovery to annihilate Native peoples.

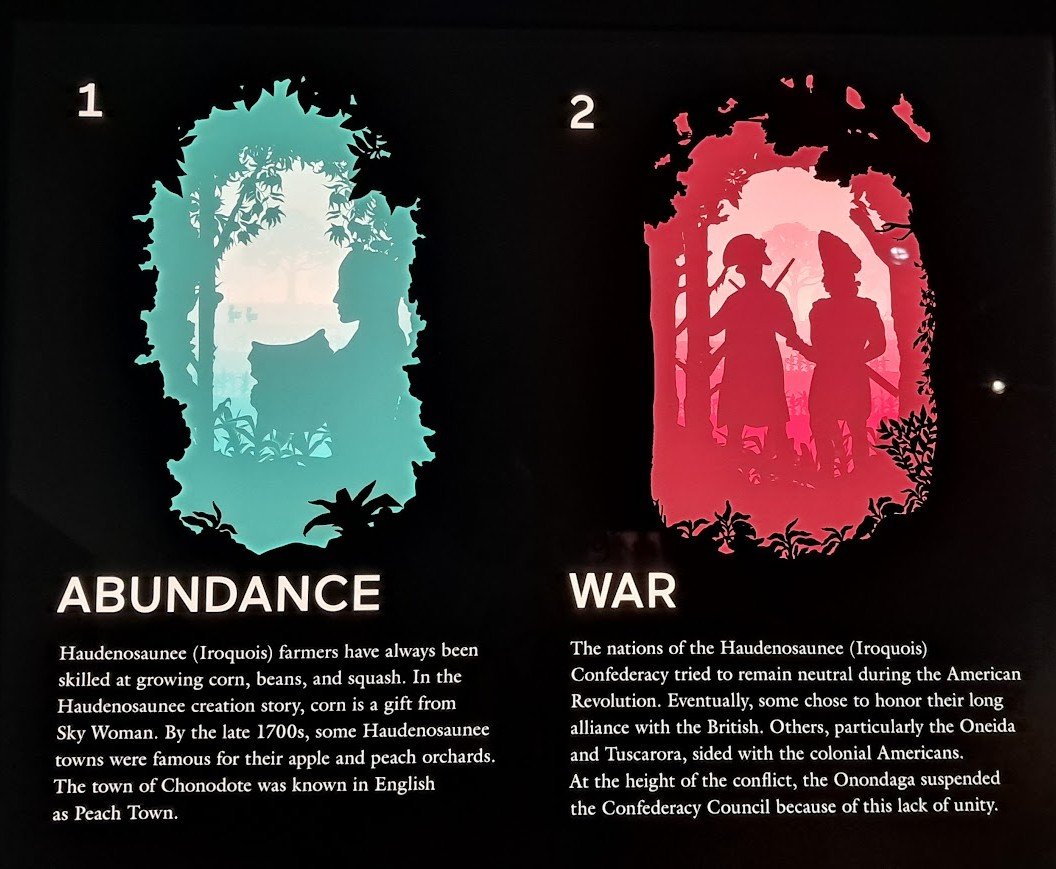

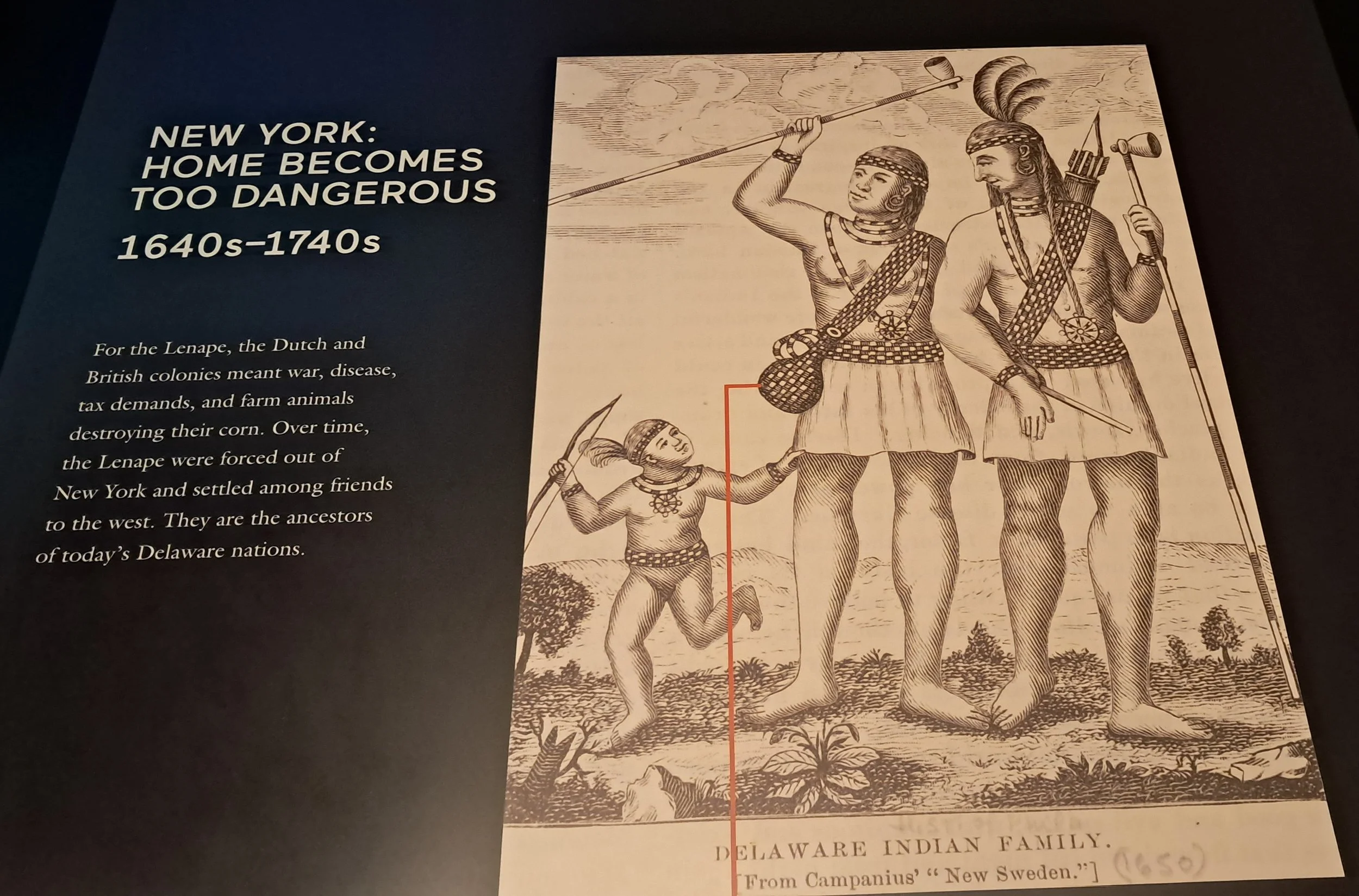

A synopsis of the abundance of life of the native Americans that later led to their cooptation with and decimation by the British and colonial Americans. (Digital illustration at the Museum of the Native American, NYC)

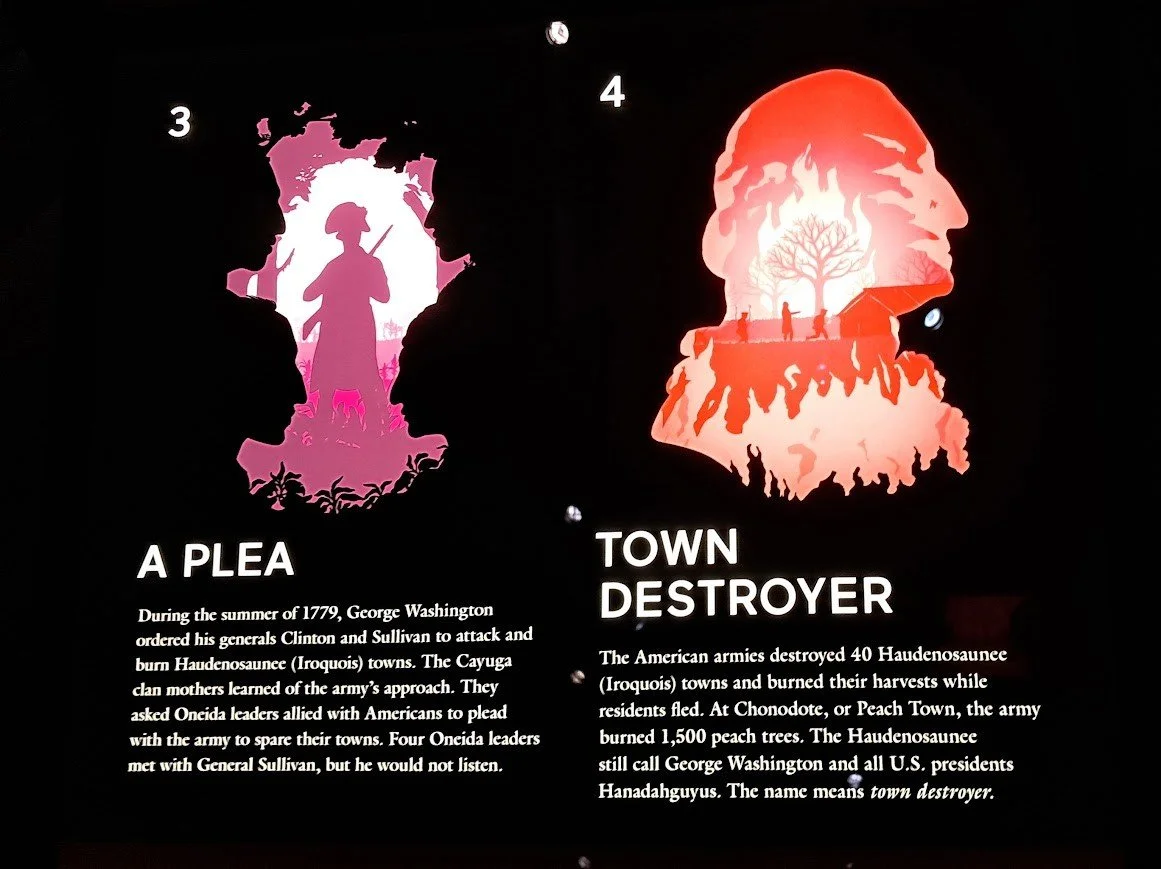

The genocide of the Iroquois nation in 1779. (Digital illustration at the Museum of the Native American)

The Cayuga nation resurrects and rebuilds itself. (Digital illustration at the Museum of the Native American, NYC)

Following the 2009 pledge of President Obama to support the UN Declaration of Indigenous Peoples which seeks to right historical wrongs, the United Methodist acted to “decolonize” the politicization of Christianity by issuing a public statement of apology to the First Nations and creating programs that bridged relationships with the Native Americas.

Contained in its Resolution 3321, the United Methodist Church affirmed the American Indian sovereignty, ensured the survival of Native People and the right to self-govern, affirmed that all persons are equal in God’s sight and natural resources are sacred and deplored practices of exploitation.

Its local churches were challenged to listen and become educated about the history of the relationship between indigenous persons and Christian colonizers in their geographic jurisdiction. Its Act of Repentance, approved in 2012, asked local congregations to encourage the training of pastors and laity to provide culturally sensitive learning environments, prioritize the Native Americans in leadership, programming, education, strategizing, and establishment of Native ministry, and transfer land or portion of land to the tribe if the UM was on indigenous territory. This was how the General Conference approached to mend and heal the relationship with Native Americans.

Following the UM inspiration, the academic sector, and local churches, I think, should continuously create, and invigorate their networks and curriculum with Indigenous peoples to share knowledge, advocate for the issues that affect them.

More pragmatically, the larger society needs to be encouraged to buy indigenous products, crafts, and goods that generate incomes for them.

Look back and heal. A story of the native Americans in New York. (Digital illustration at the Museum of the Native American)

Conclusion

Acknowledging the truth of injustice or any errant decision facilitates healing. There is no other way but that. We need to bravely confront a historical truth in America, as much as we need to do so with our own personal circumstances. The European colonizers dispossessed the Native Americans of their land, culture, and lives.

There is no real societal healing if this is not openly discussed, and genuine reparations made – from the personal to the institutional levels. All sectors and races of American society need to reach out to brother and sister Native Americans to truly promote a diverse, equal, and inclusive society in the US.

It is also time to study and reacquire the social ethics of the First Nations that uphold the equal rights of women in society. I believe that this is the way to promote balance and harmony in our social relationships.

The First Nations culture and traditions must thus be institutionalized in the academic setting, especially in response to the heightened challenges of environmental, health, and moral decay.

I believe that they have the ancient wisdom to personal peace and high regard for other people and Mother Nature, that we all can go back to - something which modern-day society is bankrupt and wanting of. All of us need to be whole again. #

Bibliography

Books

1. Haase, Albert, OFM. Albert Haase, O.F.M. 2008. Coming Home to Your True Self: Leaving the Emptiness of False Attractions. Illinois: IVP Books

2. Wimberly-Streaty, Anne and Parker, Evelyn (editors). 2002. In Search of Wisdom Faith Formation in the Black Church. Nashville, TN: Abingdon Press

3. Freedman, Estelle (editor). 2007. The Essential Feminist Reader. New York: Modern Library - The Random House Publishing Group

Interviews

1. Baguilat, Teodoro Jr. https://fb.watch/9WvBmHO_ur/

2. Davis, Patricia Anne. https://justcliqit.com/go-back-be-whole-again/

https://justcliqit.com/women-writers-of-womens-struggles/

3. Pascal, June. https://justcliqit.com/my-incredibly-unforgettable-journey-to-the-cordilleras-rice-terraces/

Online Articles

1. Baras, Ronit. Life according to the American Natives Code of Ethics. https://www.ronitbaras.com/emotional-intelligence/personal-development/native-american-code-of-ethics/ Retrieved on December 13, 2021

2. Baguilat, Teodoro Jr. Profile. https://repteddybaguilat.wordpress.com/about/

3. Davis, Patricia Anne. Profile. Retrieved on December 9, 2021 from https://nativeamericanconcepts.wordpress.com/ceremonial-prayer-shawls/ and from https://www.biodynamics.com/2016-biodynamic-conference/presenter/patricia-ann-davis

4. UNESCO. World Heritage Convention. Rice Terraces of the Philippine Cordilleras https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/722

5. LaDuke, Winona. Profile. https://www.womenshistory.org/education-resources/biographies/winona-laduke)

6. United Methodist. https://www.umcjustice.org/who-we-are/social-principles-and-resolutions/native-people-and-the-united-methodist-church-3321

7. Torah and the Environment. https://ffoz.org/discover/torah/torah-and-the-environment.html

8. Confucian Statement on the Environment. https://www.interfaithsustain.com/confucian-statement-on-the-environment/

9. The World Environmental Responsibility. https://www.bbc.co.uk/bitesize/guides/zqphw6f/revision/6

10. Native American Theories on Ethics. https://study.com/academy/lesson/native-american-theories-of-ethics.html#

End Notes

[1] Haase, Albert, OFM. Albert Haase, O.F.M. 2008. Coming Home to Your True Self: Leaving the Emptiness of False Attractions. Illinois: IVP Books.

[2] Smith, Yolanda. 2002. Forming Wisdom Through Cultural Rootedness. An essay from the book In Search of Wisdom Faith Formation in the Black Church, edited by Anne E. Streaty Wimberly and Evelyn L. Parker. Nashville, TN: Abingdon Press.

[3] Native American Theories of Ethics. Retrieved on December 15, 2021 from https://study.com/academy/lesson/native-american-theories-of-ethics.html#

[4] Torah and the Environment. Retrieved on December 15, 2021 from https://ffoz.org/discover/torah/torah-and-the-environment.html

[5] The World Environmental Responsibility. Retrieved on December 15, 2021 from

https://www.bbc.co.uk/bitesize/guides/zqphw6f/revision/6

[6] Confucian Statement on the Environment. Retrieved on December 15, 2021 from

https://www.interfaithsustain.com/confucian-statement-on-the-environment/

[7] Baras, Ronit. Life according to the American Natives Code of Ethics. https://www.ronitbaras.com/emotional-intelligence/personal-development/native-american-code-of-ethics/ Retrieved on December 13, 2021

[8] Davis, Patricia Anne. Retrieved on December 10, 2021 from https://nativeamericanconcepts.wordpress.com/about/

[9] Davis, Patricia Anne. Interview. Retrieved on December 10, 2021 from

[10] Davis. Interview. Retrieved on December 10, 2021, from https://justcliqit.com/go-back-be-whole-again/

[11] Davis, Patricia Anne. Retrieved on December 9, 2021 from https://nativeamericanconcepts.wordpress.com/ceremonial-prayer-shawls/

[12] Davis, Patricia Anne. Profile. Retrieved on December 9, 2021 from https://www.biodynamics.com/2016-biodynamic-conference/presenter/patricia-ann-davis

[13] Baguilat, Teodoro Jr. Profile. Retrieved on December 9, 2021 from

https://repteddybaguilat.wordpress.com/about/

[14] Baguilat. Interview. Retrieved on December 8, 2021 from Issues & Inspiration https://fb.watch/9WvBmHO_ur/

[15] UNESCO.World Heritage Convention. Rice Terraces of the Philippine Cordilleras Retrieved on December 9, 2021 from https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/722

[16] Pascal, June. 2014. Interview. Retrieved on December 10, 2021, from

https://justcliqit.com/my-incredibly-unforgettable-journey-to-the-cordilleras-rice-terraces/

[17] Smith, 40

[18] Smith, 47

[19] LaDuke, Winona. 2007. The Essential Feminist Reader. Edited by Estelle Freedman. New York: Modern Library - The Random House Publishing Group.

[20] Freedman. P. 407

[21] LaDuke, Winona. Profile. Retrieved on December 14, 2021 from https://www.womenshistory.org/education-resources/biographies/winona-laduke)

[22] Native People and the United Methodist Church. 2016. 2016 Book of Resolutions #3321. Retrieved on December 10, 2021 from https://www.umcjustice.org/who-we-are/social-principles-and-resolutions/native-people-and-the-united-methodist-church-3321